‘When you cannot make up your mind which of two evenly balanced courses of action you should take, choose the bolder’

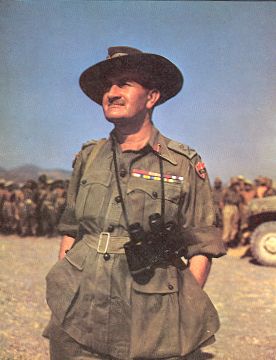

Field Marshall Bill Slim, British Army

In 2011 the UK National Army Museum conducted a poll to identify Britain’s greatest general. Bill Slim was nominated –along with the Duke of Wellington – as Britain’s greatest general. If he were alive, Bill Slim would have been surprised, as he was a modest man. His soldiers in the 14th Army (known as the Forgotten Army) fought one of the most difficult campaigns in World War II in Burma, South East Asia; a campaign fought in one of most challenging geographical terrains, against an implacable enemy, with few resources and one of the most ethnically diverse armies in British History. He led the army through one of the longest retreats in British history, transformed it and then led it to victory.

I’m not going to go into the military tactical and strategic abilities of Bill Slim – there are already some excellent biographies. I’m interested in concentrating on the person – his contribution to my understanding of leadership and how relevant he is outside the military to leadership in businesses and organisations.

Nor am I going to apologise for highlighting military leadership – this article is not about promoting war, but the view that in the cauldron of human conflict and its inherent waste, there is a place where you can learn. The leadership skills and attributes exemplified by Bill Slim are relevant to any organisation, large or small.

Slim’s 1956’s Defeat into Victory is a personal account of the Burma campaign. The initial print run of 20,000 copies sold out in a few weeks – unprecedented feat for a new author. What stands the book apart from other military memoirs is that, apart from lucid robust prose and occasional flashes of dry humour, was its disarming humility. Here was an unusual (almost unknown) species of military commander – a general ready to admit his mistakes, often assailed by self-doubt and more than willing to attribute success to others. How many recent management books produced by captains of industry reflect that approach?

Bill Slim asserted that ‘leadership was of the spirit, compounded of personality and vision; its practice an art.’ In his 1960 article in the Australian Army Quarterly (based on a lecture given to the Adelaide Division of the Australian Institute of Management in 1957, which was republished in 2003 in the Australian Army Quarterly), he defined leadership:

‘What is leadership? I would define it as the projection of personality. It is that combination of persuasion, compulsion, and example that makes people do what you want them to do. If leadership is this projection of personality, then the first requirement is a personality to project. The personality of a successful leader is a blend of many qualities: courage, willpower, knowledge, judgement and flexibility of mind.’

Slim also states that whilst the qualities outlined above are essential for good leadership, integrity is a central part:

‘Integrity should not be so much a quality of itself as the element in which all of the others live and are active, as fish exist and move in the water. Integrity is a combination of the virtues of being honest with all men and of unselfishness, thinking of others, the people we lead, before ourselves.’

In On the psychology of military incompetence, Norman Dixon writes that great generalship depends on an absence of authoritarianism:

‘Firstly he was non-ethnocentric and therefore able to achieve the almost impossible, but vitally necessary, goal of maintaining a good relationship with Chinese allies, however frustrating they may on occasion have been. By the same token, his brilliantly successful leadership of Ghurkas, Africans and Indians, as well as Europeans (the14th Army was probably the most multi-ethnic army in British military history), would have been impossible had there existed a trace of ethnocentrism in his make up.’

Slim had the capacity to maintain good relationships with ‘difficult’ people – and, in particular, fostered inter-service partnerships, promoting a culture where collaboration was the operational norm.

In my professional career I’ve dipped in to and studied many of the management publications on leadership, considering areas like authentic leadership, servant leadership, democratic leadership etc. Often, I have found there is a tendency to encourage a scientific and structured approach with models to follow, including training programmes to develop the skills – which has always struck me as mechanistic. Slim believed that the best training for leadership was leadership. He, also through his actions, maximised the use of ‘soft skills’. The only model for me near to the approach exemplified by his leadership is Appreciative Leadership, created by Diana Whitney, Amanda Trosten- Bloom and Kae Rader. Appreciative Leadership linked with the organisation development philosophy Appreciative Inquiry is defined as:

‘A relational capacity to mobilise creative potential and turn it into positive power – to set in motion the positive ripples of confidence, energy, enthusiasm and performance – to make a difference in the world.’

The authors, writing in the AI Practitioner, Volume 13: Number 1 (Positive and Appreciative Leadership 4) explain that leaders who use the OD philosophy Appreciative Inquiry as their vehicle for positive change have four things in common:

- They’re willing to engage with other members of their organisation or community to create a better way of doing business or living

- They are willing to learn and to change

- They truly believe in the power of the positive

- They care about people, often describing the work of the organisation or business of helping people, grow and develop

If you study Bill Slim’s leadership, you’ll see connection and resonance with these four elements. Studying Bill Slim has served me well – better than attending any leadership course and much of the leadership theory practise I have read. Here are my key learnings:

- – The importance of clarity of intention: delegation fosters quality work, commitment, learning and innovation

- – The value of creating a learning culture: providing the maximum potential for training and fostering a professional operational framework

- – Be accessible: foster a simple and understandable message; be out and about and communicate clearly

- – The importance and value of sharing stories as a way to learn and communicate

- – The value of developing quality relationships and fostering collaboration in creating well-led and effective organisations

- – The importance of supporting a non-blame culture that encourages learning from errors, to take calculated risks and be bold

- – Adaptability, innovation and flexibility are created from fostering energy, and supporting a culture founded on trust and confidence

- – The recognition that leadership is an art and not a science, and that it’s about the combination of spirit, personality and vision. Successful organisations need leadership at all levels

- – The value and importance in caring for staff, encouraging their wellbeing and the way this can support organisational effectiveness

- – The value of time for reflection: accept all success includes other people and learn to be more resilient

So, what is Slim’s relevance today?

I first came across Slim’s Australian Army Quarterly article in Russell Miller’s Uncle Bill. Miller says:

‘It would foreshadow the advice of legions of management ‘experts’ in the years to come. Indeed, nearly 50 years later, in 2003, a transcript of the lecture was published in 2003 in the Australian Army Journal with a note ‘It is amazing to consider how many ideas in this article have been sold in recent books as novel new approaches”‘

One quote from Slim particularly resonates:

‘Some invention, some new process, some political change may have come along overnight and the leader must speedily adjust himself and his organisation to it. The only living organisms that survive are those that adapt themselves to change.’

Yet we still have not responded well to the ideas expressed over 50 years ago!!

Studying Bill Slim – and my more recent use of the OD philosophy Appreciative Inquiry – have shown me the importance of working from strengths, fostering adaptability, flexibility and wellbeing. He was an exponent of the appreciative and conversational leadership model and has and will continue to provide encouragement and sustenance in my leadership journey.

The lessons learned, actions taken and leadership skills provided by Bill Slim and his 14th Army in Burma over 70 years ago have much to teach us in these challenging times, countering the prevailing views of control, risk averse and zero mistakes and errors.

Tim Slack

For more information about our leadership training and board development work, please contact Tim Slack by email.

Comments are closed.